The Afterlife of Technologies in Society

Do technologies ever really die? In many ways they live as ghosts in our societies and help us move forward.

It hangs on a wall in a nook in the kitchen, a sort of relic or ode to the past. It still works too. Even in a power outage. It rarely gets used or even thought about, for it rarely, if ever, even rings. An old telephone, connected with copper wires a redundant back up system. I keep it on purpose. Its cost negligible.

Many technologies have a sort of afterlife and live on in ways we rarely think about but have deep cultural roots that can last decades or even centuries after the initial technology has evolved or been replaced.

How often do you click on the “save” icon in a word processing app to “save” your work? That icon is from the days of the floppy disk where you did have to click it fairly often or you’d lose your work in a crash. And PC storage was minimal so we used floppy discs.

Oh and inside your smartphone is a feature called a phone, and we still “dial” just rarely with numbers and we “hang up” even though there’s no physical handset to slam down. In those days, when we were angry over a call we could slam down the handset and feel rather chuffed about doing that. Now we might throw our smartphone onto the floor. And have to pay for a new screen.

When we’re on YouTube or another video channel and we “rewind” the video or “hang up the phone we’re preserving certain elements of culture and in some ways, transmitting culture from one generation to another. A Millennial or Gen Z today hears the stories of older generations through these references. And in odd ways, carry that language forward.

In part, the way we refer to aspects of technologies we rarely, if ever, still use acts as a teaching tool and maintains a degree of social continuity through all these disruptions. Beyond teaching they also serve as a way to help us understand and use new technologies that have evolved from the old ones.

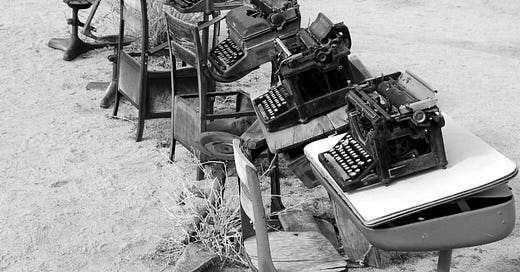

We still organise files in “folders” and the QWERTY keyboard layout lingers from the days of typewriters going back centuries. This is embodied cultural knowledge. It’s not just nostalgia, it shows how deeply embedded in material culture a technology became in our cognitive processes.

In our language of technologies that have evolved, we still reflect power dynamics in a way. Think of all the various apps you use at work or play. They all have administrator/user and permissions terminology that reflects deeper social patterns. In a way, subtly, these interfaces preserve and reinforce social relationship dynamics.

Consider that even with electric vehicles we still talk of horsepower in terms of energy. We still roll down our car windows even though we’re just hitting a button. While this language use persists, we are seeing technological “deaths” happen faster than before in the digital age.

In the pre-industrial era, technologies often lived on for centuries, so gradual their “death” that it’s hard to this day to say precisely when they died. Like water wheels and windmills. Some of which still are used just in very small instances.

As we moved into the twentieth century, the pace of technologies “dying” became faster. The decline of the telegraph took 50 years. But it didn’t entirely disappear. The telegraph was the foundation for the telex machine, which also took decades to fade. These technologies died slowly because socioculturally, we still operated through mechanical means.

By the time of the mid-twentieth century, a fairly short span, technologies became obsolete or declined much faster. Vinyl records took about 20 years to be replaced by CDs, though there’s a small resurgence of vinyl for niche markets. Touch tone phones replaced rotary dial in 20–30 years. It took about 15 years for electronic typewriters to be replaced by word processors.

As we entered the end of the twentieth century, technology obsoletion ramped up even more. Floppy disks were gone in about a decade or less. The Palm Pilot and similar organising devices only lasted a few years until the Blackberry, then iPhone, replaced them. Within a couple of years of the rise of Facebook, MySpace was largely gone. Though it lingers in digital purgatory.

Today, in the first part of the twentieth century, while some technologies persist, some are replaced even faster. Mobile apps can have a lifespan of just months. Social media platforms can be the same. Like Clubhouse. Web3 apps are there, but live in a liminal space, struggling to gain traction, even though they hold much promise.

Software dies faster than hardware, which dies faster than infrastructure. Consider though, that much of the global financial system runs on COBOL, a computer language from the late 1950s.

Much of how we relate to and understand newer technologies is through metaphorical references. Hence still using the floppy disk icon for “saving” our work. We like this notion that when a technology dies it is gone. Yet many become some sort of “technological ghost” and we see traces of them linger in our language and in software references.

Technologies have a remarkable way of persisting in our sociocultural systems though language, power dynamics and information networks. In some way, they serve as vital threads in our cultural fabric. We stitch them in with language and literature, the stories we tell.

This isn’t a bad thing. It is not a failure of progress, but rather a way of how we build meaning through so many layers of accumulated experience, personally and societally. In a time of unprecedented technological change, including, of course, AI, these technology ghosts may, in some ways, be teaching us about what it means to be human with technologies.

We are creatures, animals, who understand our present moment through the stories and whispers of what came before.