Are We Creating a Global Monoculture? No. Why Not?

The surprising ways digital technologies from smartphones to social media, are preserving cultural diversity globally.

Nguyet, grandma to Linh, was teaching her ancient family recipe to Linh. She was using the smartphone Linh had given her, speaking in Vietnamese with English subtitles, all while wearing her traditional áo dài and Nike sneakers. Within days bloggers in São Paolo and teens in Detroit were trying out her recipe. All of them debating the spices, making alterations, chatting about them on social media, sharing their own videos.

Here’s the paradox. A 73-year-old woman in Vietnam using a smartphone to share a deeply traditional dish, but rather than creating cultural homogenisation, it resulted in an explosion of local variations around the world and inspiring others to share their traditional dishes.

People often comment to me and I hear and see it in my travels. A fear, or concern, that we are creating some sort of global monoculture. That we’re losing our various customs and traditions, flattening into some sort of monochrome beigeness.

As an anthropologist, I’d argue this isn’t the case at all. That in fact, this connectedness via digital technologies is helping us discover that rather than erasing and blending our differences, these digital tools might just be helping us discover just how beautifully, stubbornly and creatively distinct we really are. And that’s quite magical. So why do I think this is so?

This fear stems from anthropologist Lévis-Strauss’s theory of bricolage (the way cultures blend cultural materials to evolve), but in this case is what I call a “bricolage fallacy”, mistaking the sharing of cultural elements (foods, customs, fashion, music etc.) as cultural appropriation or homogenisation into some bland sameness. It’s a fallacy because this is not the case. At all.

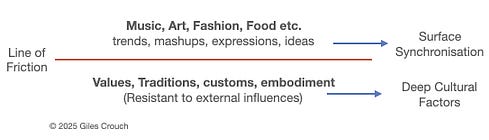

What I think we are seeing is a type of “surface synchronisation”, shared aspects of a culture, like foods, music and dance moves, but they only slip and mix into other cultures at a surface level. You may try that traditional recipe, but you’ll probably adapt it somewhat to your cultural and local preferences. Same with dance moves, political systems, traditions. This is where we see the role of friction in cultural transmission come into play. And that’s very important.

Consider a global restaurant brand like McDonald’s. While those golden arches may be the same around the world, look deeper and you see cultural adaptation. They serve wine at McD’s in France. In India, the emphasis is on vegetarian options at the front of the menu.

Cultural translation never creates or results in a perfect mirroring of another culture, something again noted by anthropologists Margaret Mead, Claude Lévis-Strauss and James Watson, more recently, in his book about McDonalds.

Another example is the Danish concept of “hygge” which is all about coziness. It went viral globally a few years ago. But rather than copy it exactly, people put their own local twists on it. The German concept of “gemütlichkeit”, the African philosophy of “ubuntu” and Japanese “ikigai”, all with their own cultural twists.

This is a form of friction that is often seen as bad, since it generates “heat” (culturally in this sense) and thus is a factor like entropy, which results in decay. But in this case, this cultural friction is a good thing. The friction creates creative tensions, which results in new cultural forms rather than a sameness across multiple cultures. Digital friction creates differentiation, not convergence.

And if you’re thinking, rightly, that social media platforms through algorithms, are creating a set up for global cultural homogenisation, in reality, they aren’t. TikTok, Instagram, Snap, Facebook, those algorithms account for local, cultural preferences. I know, seems counterintuitive.

There are limitations to digital communication that have significant impacts on cultural transmission. Culture, a complex word, is very deep. No digital technology, not even AI like ChatGPT or Claude captures spatial relationships, smells, scents, flavours, or micro-timing in social interactions. Digital tools are great for some forms of visual, textual transmission, but none can translate what it’s like to dance, to “feel” the experience of another culture. They are mirrors only.

Take for example, a Japanese tea ceremony shared on Instagram, which may capture the visual aesthetics but misses the micro-cultural actions embedded in hand positioning, breathing patterns, seasonal awareness. In anthropology, such “actions” are called embodied and no digital technology can do that. So this is the “friction” between digital representation and embodied practice, which strengthens the local, physical culture.

Digital tools then are creating more sophisticated forms of cultural resistance, not less. Indigenous communities around the world are using social media not to assimilate, but to coordinate cultural preservation efforts, sharing their traditional knowledge in protected ways. Often building solidarity networks that strengthen local practices.

Friction between global technological tools and local cultural content creates hybrid forms that are more resilient than either pure tradition or pure globalisation. If our global cultures were really homogenising, we’d expect to see random distribution of cultural traits across networks. Instead we are seeing “preferential attachments” where cultural practices cluster and we see new forms of what we call in anthropology “imagined communities.”

K-pop fans around the world don’t just consume the music, they learn Korean words, adopt Korean beauty standards and learn about Korean social hierarchies. These digital networks, subcultures if you will, create friction that pulls people deeper into cultural orbits, not into a generic global average.

Cultural friction in digital spaces generates new forms of cultural expression that are simultaneously global and local.

Digital friction acts like the grooves in a vinyl record — without the resistance, you get no music. The friction between global platforms and local cultures creates the “music” of contemporary cultural diversity.

So in the end, we might say that this digital friction, this transmission and sharing doesn’t threaten cultural diversity. Rather, it is the mechanism by which cultures become more distinct within a global context. So take heart, we are not headed towards a sea of sameness. We are continuing to be human, in wonderful, creative, messy and unpredictable ways. Isn’t that beautiful?

The internet is primarily an American artifact with all the rules and US advantages and homogeneity you would expect from such a centralized system. These are platforms that serve American interests and algorithms owned by huge corporations that certainly have limited respect for global culture or diversity.